The far right and populism pose a threat to democracy

NewsTogether with Daphne Halikiopoulou, a Professor of Political Science at University of York, we explore the rise of far-right populist parties and why the pose a threat to democracy in Europe. Halikiopoulou, a well-known researcher in the field of far-right politics and populism, describes the rise of the far-right parties in European and Nordic politics as worrying. For that reason, they must be stopped, she points out in FinUnions’ interview.

The vote share for populist, and especially for far-right populist, parties has increased significantly across Europe. In national elections last year 32% of European voters opted for an anti-establishment party compared with 20% in the early 2000s and 12% in the early 1990s.

“There is a trend of more support for the far-right. The bigger problem is not just the vote share but also the entrenchment of the far-right parties in the system”, Daphne Halikiopoulou explains.

These parties have proliferated. She recalls the situation back in 2012 when, in the aftermath of the economic crisis, commentators were comparing Greece which experienced the dramatic rise of the neo-nazi Golden Dawn with countries such as Spain and Portugal that also suffered the severity of the economic crisis, but had no successful far right party at the time.

“Which country does not have a far-right party in Europe these days”, she asks.

A quick internet search reveals a variety of far right and nationalist parties. To mention a few, the list includes the radical right Vox in Spain, Fidesz in Hungary, United Right in Poland, Portugal’s Chega, the French Rassemblement National and many more. On the extreme end of the spectrum, there are also the ultra-nationalist far right parties, often described as neo-nazi. Among these are the Golden Dawn in Greece (now incarcerated), Slovakia’s L’SNS, Croatia’s Party of Rights or Germany’s NPD etc. The list is long, too long.

“The number of far-right parties has tripled. And many of them are now in government. This is a very worrying sign”, Halikiopoulou adds.

Nordic democracy in crisis?

Looking at the Nordic countries, which are often considered as “front runners of democracy”, we see an equally worrying trend: growing support for the Sweden Democrats in Sweden, the Danish People’s Party and the Progress Party in Denmark and the Finns Party entering the Government in Finland. What does this say about the state of Nordic democracies? Do we have a democracy crisis on our hands?

Halikiopoulou regards these changes as dangerous for democracy in a broad sense. She sees the increasing entrenchment of these parties in their domestic political arenas much as a result of the willingness of other political actors to treat them as legitimate competitors.

“We saw it with the Sweden Democrats and it’s a total breakdown of cordon sanitaire*. We saw it in Finland, with yet another inclusion of the far-right in government”, she comments.

On top of this you have the radicalization of the center-right. Many center-right parties are moving towards the right to compete with the far-right. The professor and other fellow researchers consider this as a very dangerous path for democracy.

“Unfortunately, the public is also becoming more tolerant of the populist far-right. There are many reasons for this. People are willing to trade off democracy, maybe because they think the leaders could bring about economic stability or because they think they could address crime or migrant issues. This is a trend across Europe. In this sense, the Nordic countries are especially concerning, because we see a breakdown of the cordon sanitaire*, which we did not see before”, Halikiopoulou adds.

Protest voters are increasing.

Daphne Halikiopoulou also brings up a recently published research project focusing on discontent with democracy and distrust in institutions as drivers of far-right support. The findings are interesting.

“We do find in this study that discontent with democracy and distrust of political institutions is linked to the rise of the far-right”.

She breaks it down:

“What this means is that people are discontent with the establishment and with mainstream parties. They may feel that mainstream parties in government are not capable of delivering their social contract obligations. And so, the vote for the far-right is an anti-establishment vote, a so-called anti-vote”, she explains.

People expect far-right voters to be ideological voters, nationalists, and anti-immigrant, but this is not always the case. Not anymore. An ideological voter is attached to the party for ideological reasons, but according to the professor staunch far right ideologists are few in numbers. She stresses that the far-right voter pool also consists of voters who are discontent and distrustful and vote for the far-right as a protest.

“What I found very interesting in the research is that for those fewer ideological nationalist voters, trust works the other way. Where the system is considered part of the nation and people are proud of them – take the Nordic countries and their Nordic Model for example – they would like to preserve it for themselves. The mechanism works the other way. That is why it would be interesting to look closer at the Nordics”, she points out.

No typical far-right voter

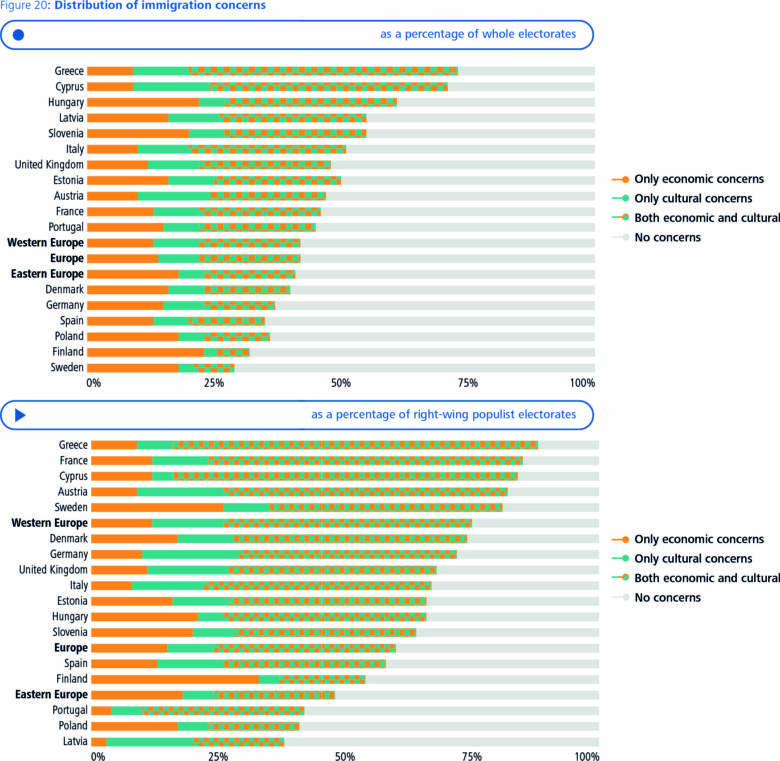

Halikiopoulou’s research suggests that there is no typical far-right voter. Immigration is one factor driving voters to support the far right, but it is not the only factor. In addition, immigration itself is a muti-faceted concept: whilst some voters may oppose immigration for cultural reasons, others are driven by economic concerns.

“Far right parties share a common emphasis on nationalism and propose nationalist solutions to all socio-economic problems. Immigration has been important to these parties because their core nationalist ideology centres on the distinction between the in-group (natives)and the out-group (migrants and those who don’t belong). But as these parties have grown electorally, they have also become broader ideologically. My research shows that one of the reasons why they are successful is because they can link immigration to a broad range of societal problems”, she explains.

Halikiopoulou elaborates:

“If people have economic concerns, the far right says ‘we’ll address these by getting rid of the immigrants’. If people have welfare- related concerns, they say ‘we get rid of the immigrants’. In other words, they can link immigration to many different societal issues that concern voters. Therefore, they are much more multifaceted than what we might think”.

Halikiopoulou and other researchers often use European Social Survey (ESS) data to examine the individual level factors that drive far right party support.

“One of my articles shows that roughly one third of the far-right electorate reports having no immigration concerns at all. In another study we have found that out of the ones who do have immigration concerns a very substantial number reports these concerns to be economic-related. There is the fear that immigrants are competitors in the labor market, in welfare provision and social services”, she explains.

According to the professor, the one third that report no immigration concern at all, is probably the distrustful voters. These voters can be taken back, while the ideological voters stick to their party(ies). All the distrustful voters, who are economically affected can be persuaded.

The role of the cost-of-living-crisis

Halikiopoulou’s research suggests that Finland is one of the countries where the far-right voter pool consists of many voters with economic concerns over immigration.

“As a result, the Finns party strongly emphasizes the economy in its nationalist narrative. It is not possible to fully disentangle the far-right in Finland from the economy.”

Halikiopoulou stresses the importance of trust in institutions and effective policies. The research looks at many indicators such as trust in domestic institutions, but also at trust in policy. What it comes down to, is an overall question of democratic representation and ability to deliver on social contract obligations.

“The article that I co-authored with Tim Vlandas examines the role of social policies. In countries where specific social policies that compensate various insecure groups are in place, the insecure groups are less likely to vote for the far-right”.

This is very interesting as it does not apply to the Nordic context. The Nordic countries are very strong welfare states compared to other parts of Europe. Despite of many policies being in place, there is support for the far-right.

“I suspect that it has something to do with the findings that I referred to earlier. Because of the identity question and having embedded welfare into nationalism and national identity, there is a dynamic of more trust and more far-right”.

Sleepwalking into democratic backsliding

When asked about the broader implications of far-right party success across Europe, Halikiopoulou described the problem as ‘sleepwalking into democratic backsliding’. This, she suggested, works on two levels. First, there is the normalization of hate.

“If we, the public, accept or endorse a far-right party, we are a step less tolerant. That normalizes the extremists”, she says.

“Second, on an actual organizational level, I do think – from anecdotal evidence, from personal relations and people I have spoken to – that many far-right parties, even ones that appear more normalized, have links to extremists’ groups. The networks are in place, and they are working”.

An additional problem is, as we can see in public discussions, that often far-right narratives are increasingly adopted by center-right parties.

The professor sees this as a very dangerous route towards undermining democracy. Tolerance for the far-right among the public is likely to grow, and as a result hate crimes may also increase. Even more worryingly, populists in power implement exclusionary and intolerant policies designed to outlast them.

“Look at what Donald Trump did, and what Victor Orbán is doing with the judiciary. They put institutional mechanisms in place that are very difficult to get rid of and which will last for a long time”, she mentions.

Focus on the real problems that need to be solved.

What can be done about this?

The professor advises against falling into the trap of reproducing far-right narratives. Instead, parties need to focus on finding solutions to fundamental problems in society. There are plenty, adding the energy crisis and inflation to the long list.

“The Left must not platform the far-right. We cannot enter coalitions with these people, we must not play ball at all”, she stresses.

Far-right parties have been able to put forward appealing narratives, which has added to their success. Unfortunately, this has not always been the case for the left, which sometimes appears divided, positing answers in a less appealing way.

“This comes across. But copying the far-right is not a solution and it does not work or attract voters”, she emphasizes.

When it comes to social media, or broader party campaigns, Halikiopoulou says left-wing parties need to be the agenda setters, instead of responding to the far right or simply defending their positions.

“A party’s electoral performance largely depends on what other parties do. Talking a lot about an issue a party ‘owns’- for example immigration in the case of the far right- increases the salience of the issue and pushes voters closer to the party that owns the issue. In other words, excessive talk about immigration will not favor the left. It is not a winning strategy.”

A complex relationship.

Co-operation between the trade union movement and the far-right is strenuous. Halikiopoulou shares some light on this complex relationship. While in many ways the two movements are ideologically antithetical, far-right parties often utilize worker narratives, for example emphasizing the welfare state, to become more appealing. These parties compete directly with trade unions, and in times when union membership numbers are declining, try to seize the opportunity to gain support from workers.

“When it comes to economic policy, there are two types of far-right parties. There are the ones that follow a neoliberal line, for example the PVV in the Netherlands or the Front National (FN) during the leadership of Jean Marie Le Pen in the 90’s in France. Then there are the ones following a very pro-welfare and pro-worker position. An increasing number of far-right parties now adopts pro-welfare narratives, like the Rassemblement National (RN, previously FN) since Marine Le Pen took over” she explains.

“No wonder the French party leader Marine Le Pen comes across as a savior when she says the party cares about economically disaffected people and workers. What people need to keep in mind is that this is a fake narrative and the party clearly racist”.

Another example is the Greek Golden Dawn, a clearly a neo-Nazi party which centred much of its economic narrative on the welfare state, even offering soup kitchens and alternative provision to native Greeks (only after the presentation of a valid Greek identity card) during the economic crisis.

We concluded the interview with a discussion of Brexit in the United Kingdom, which Halikiopoulou described as an important example of the broader trend towards right-wing radicalization.

“There is no successful far right party in the UK right now. But this is only because there has been an overall shift to the right” Halikiopoulou says.

“Brexit happened because Prime minister at the time, David Cameron, wanted to compete with UKIP and appease the more right-wing elements of his party. It was a huge miscalculation. To compete with the far right, in many ways the Tories became the far right” she says.

Donald Trump taking over the leadership of the Republican party around the same time can be seen as part of a broader trend towards right-wing radicalization.

Although some of these developments have been stalled or overturned- e.g., Trump has lost power for now and PiS was recently outvoted in Poland- the far right remains powerful and entrenched in many countries across the globe.

“This is a very worrying trend for the future of our democracies”, she concludes.

* The policy of marginalizing extreme parties.

Photo by Daphne Halikiopoulou.

Daphne Halikiopoulou

Born in Athens.

Living in London.

The best thing about London is that the city is always buzzing, the worst thing is the rain.

I’m passionate about the sea.

If I was not a researcher, I would be a travel book writer.

N.B.!

Welcome to join FinUnion’s seminar “How to deal with the “Far-Right Populism in Europe?” on 7th of November in Brussels. The seminar will explore different options for dealing with right-wing populist forces ahead of the European Elections in 2024. We discuss challenges, strategies, and experiences together with top experts, Media, and trade union representatives.

The keynote speakers for this event are Daphne Halikiopoulou, Professor, Chair in Comparative Politics, University of York and Yannick Lahti, Populism Scholar at the University of Bologna. Register here by 27th of October!